Investment in industrial research

Productivity is dependent on not just the investment in research, but the implementation of new technologies that increased profitability. A new report from the Dallas Fed points out that there is a way a state can foster increases in productivity from new technological investment, which is funding federal industrial research programs. In Canada, we have not done this in a way to foster actual productivity gains.

Investment in R&D

There is a direct connection between federal research and development funding and productivity. So says the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Canada has had a declining investment in industrial R&D at both the federal level through cuts to the National Research Council and the corporate level, through lack of investment at the firm level in technology upgrades.

Part of the government's response to this was to follow the terrible advice of the OECD, IMF, World Bank, and other major international policy shops to smash the pillars of industrial, corporate, and firm-level research together into the university system. The goal was to get professors and their graduate students to focus on commericalization of their research directly.

The added benefit of this new paradigm was that it would save government's money on the industrial side while reducing setate-level regulation of private capital (one of the main jobs of government funded industrial research).

This worked for a while, but not because of the policy. The impact of the cuts were not noticed because they happened just as the Dotcom bubble was inflating, artificially pumping-up productivity numbers.

Since the deflation of that financial bubble, governments have been pushing harder on the neoliberal program of cuts to government research programs and shifting to profit subsidies, only to find they are not resulting in the productivity gains that were promised.

This new research has looked at government research programs and found that domestic, non-military public research and development focused on industries has a return of 150 to 300%. More than investment in infrastructure spending, which they estimate as 25%.

Non-military R&D spending focused on industry is two to six times higher than military R&D spending in the USA when it comes the impact on the economy.

R&D and Productivity

The best thing about industrial R&D is that it has a huge positive impact on total factor productivity.

Why do we care?

The reality is that Canadian firms have not been huge on investing in productivity gains. This is mostly because of the make-up of our economy and the low level of wage growth since the 1990s. An economy built on resource extraction does not need to invest in productivity increases since profitability is barely impacted by wages (especially slowly growing wages).

The other issue is that Canada is a country where direct foreign investment is rather huge. And, that foreign investment only likes to own things, not invest in productivity gains. Especially, during economic slow-downs—of which there have been many since 2000.

The response is clear. If Canada wants to increase its total factor productivity, we need to do at least two things:

- Invest in public industrial research and development.

- Expand investment in productive capacity.

Luckily we know the ways to do this:

- Invest in our National Research Council with an eye to public production.

- Increase wage pressure on companies so that they increase their investment in machines that replace workers (Organic Composition Of Capital).

"Hang-on," you say. We want companies to replace workers with machines? Well, not really. But, in Capitalism they have to if firms want to compete, so as workers struggle against employers they must extract these concessions.

Canadian research funding support

Canada has been spending a lot (incorrectly) for a while now on business innovation and growth supports (BIGS). BIGS is a funding program to support private-sector research and development, so called "innovation".

The issue is that the Canadian government thinks that profit subsidies are the best way to do this.

Statistics Canada released a study into the effect of this spending on the desired outcomes (i.e., more R&D spending and increased profits).

They broadly show that the support did not achieve the desired outcomes. No shock there to anyone who has been paying attention.

The findings are a little underwhelming:

- profit subsidies likely supported firm revenue and employment

- profit subsidies had a negative impact on general profit generation through covid. (i.e., profit subsidies supported unprofitable firms through the pandemic)

- profit subsides have small impacts whether negative or positive.

- More profit subsidies went to firms who made stuff for the domestic market.

- American-owned firms did more actual R&D with the profit subsidy than Canadian-owned firms. This is also just a consequence of the type of firm owned by Americans.

_in_millions_of_dollars_chartbuilder.png)

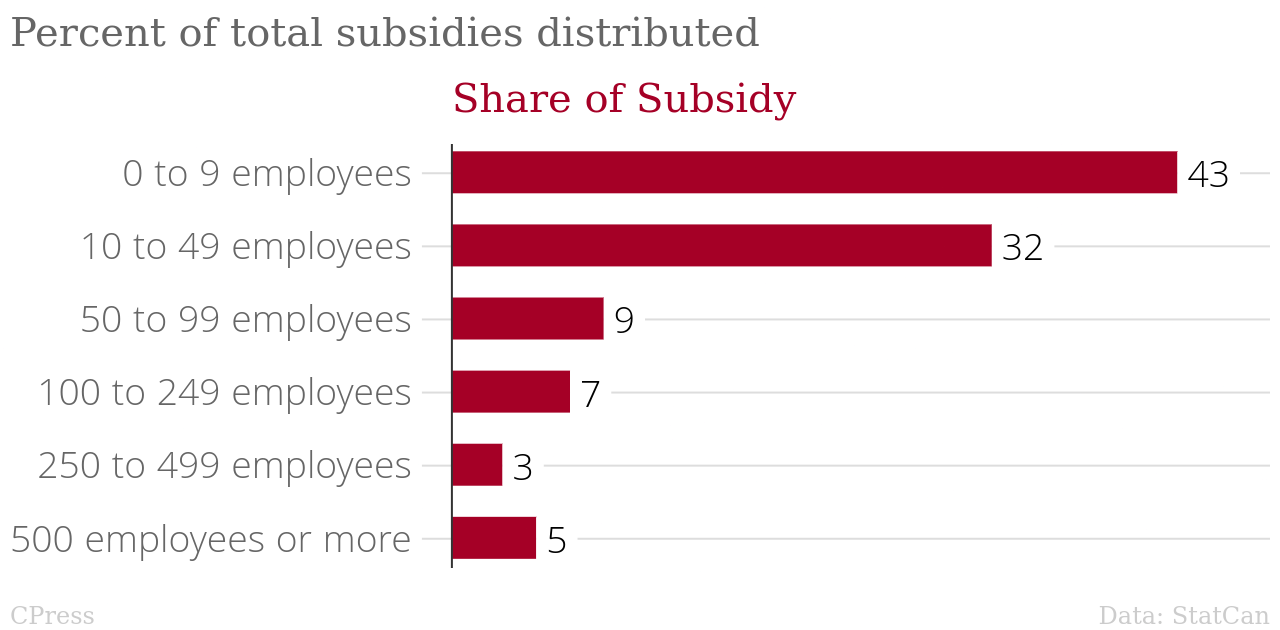

Most of the profit subsidy has gone to smaller firms, also known as "start-ups". We used to call these firms "small businesses". Either way, they are firms known to fail way more often than succeed. They are also firms not really large enough to leverage these profit subsidies into anything meaningful in terms of production.

Most of the money has gone to manufacturing and "professional services". For manufacturing, those are the larger firms receiving the subsidy.

Part of the problem here is the policy expectation of profit subsidies attempting to drive innovation.

We know from previous studies in the USA and elsewhere that the best way to drive investment in new things is to provide firms clear and easy answers to questions of achieving increased profitability with new technology.

Such a program is outlined by publicly funded industrial research, like that which happens in the National Research Council or in ministries like Natural Resources Canada.

Giving firms who focus on making something money to invest in research and development to innovate processes they already implemented is generally pointless. Private firms are generally not full of researchers who can do things with this money, unless they are structured that way from the get go.

One of the reasons we see increased revenue, but not increased profits from Canadian firms who take these profits subsidies is that they grow fast because of the government subsidy, but likely faster than the market can deal with. Or, more, faster than they can deal with. The subsidy essentially drives unsustainable growth.

This is not surprising from a classical perspective of the economy. But, it sure surprises the heck out of orthodoxy economics policy makers.

The take home? Canada should stop giving money away as profit subsidies and instead fund the NRC and other industrial research programs, develop an industrial strategy, and help firms invest in desired production and reap the rewards of the corresponding productivity gains.

But, to do that, we would need a real investment program, not just a profit subsidy regime.

Wages, automation, and industrial strategy

The concession of an Industrial Strategy that involves industry-focused research on production is important for workers on two fronts.

- We need to make sure that wage gains that results in workers being replaced with machines happens through a process that incorporates a just transition. And,

- that the machines that replace workers are made in the same place employment is affected.

"Just transition" here means financing all the social programs that support workers moving from one job to another so that there is no negative impact on the individual worker and their family. This protects the community.

Only through this process of democratic industrial policy and strategy development can we ensure that the impact of automation does not result in massive local job loss and economic shifts.

In the absence of industrial strategy and true just transition, workers end-up paying for all the economic benefits of automation and it ends up just being outsourcing. In the absence of an industrial program, it is up to the working class to push back and oppose automation of their employment.

You see the issue? We do not have an industrial strategy and so people are very angry and worried about the impact of automation on their jobs. The history of capitalism is that there is not support for those who lose their jobs, and so there is no support for productivity gains.

Workers would rather have low wage growth than be tossed aside through automation.

We have a choice, but it is not going to be given to us. To have the future that we need that provides efficient use of natural resources and increased leisure time, capital must not be allowed to continue to use automation to transfer wealth from workers to themselves.